Invisible Magic

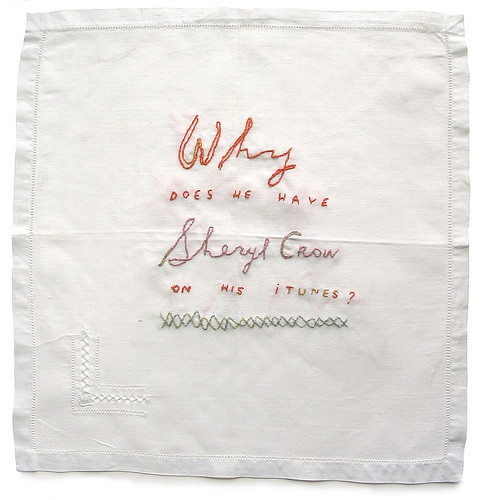

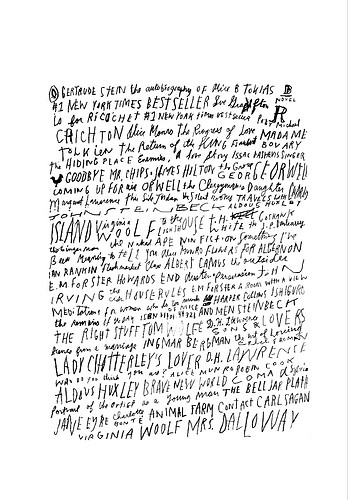

I couldn’t help but nod in agreement as Stefan described this deal he made with himself via the visual indications surrounding him. I, too, depend on what I consider objective signals from impartial sources to forecast or forewarn how a particular situation or encounter might unfold, and I consider all forms of communication fair game. Bumper stickers, t-shirts, snippets of eavesdropped conversations, fortune cookies, newspaper headlines, errant flyers, songs on the radio: these are all potential messages specifically targeted to foretell the future ahead of me.

I think most people participate in some sort of similar behavior; in fact I suspect we engage in a raft of puzzling rituals far more than we even realize. Who among us hasn’t crossed their fingers or knocked on wood or avoided walking under a ladder or tossed salt over their shoulder in the hope that somehow these corny compulsions could protect us from doom or despair?

These superstitions ultimately signal an utter disregard of reason. The superstitious person is under the false assumption of a divine or paranormal influence or form of control over the universe. But superstitions work both ways, for all of the little rituals one might engage in to ward off evil, there are as many that instill a belief that nothing will ever change, and that all the luck we are levied will continue flooding in forever. As a result, the athlete on a winning streak might not change his socks or shave and a gambler might need to sit in a certain chair in order not to break the spell of good fortune. Why do we do this? What is the reason we instill so much power in these signs, these rituals, these amulets of supposed power or protection?

In the case of athletes, sports doctor Richard Lustberg states that “superstitions create a confidence inside a player or coach. Athletes begin to believe, and want to believe, that their particular routine is enhancing their performance.” Wanting more control or certainty is the driving force behind most superstitions. Freud called superstitions "faulty actions." Modern psychologists call this “magical thinking.” Some consider superstitions expressions of inner tensions and anxieties. And still others believe superstitions are signs of a mental disorder.

Mental disorders notwithstanding, lately I have had a hard time not feeling particularly superstitious. There seem to be signs all around us of impending doom. While most days I try to buoy myself up with optimism and high hopes, there are those intermittent spates of days that pop up and challenge all facets of idealism. When is the war going to stop? When will the troops come home? When will the Katrina victims all be housed? When will we find a cure for Aids? Or Alzheimer’s or Multiple Sclerosis? It seems narcissistic, even mad to consider that an enthusiastic billboard or encouraging fortune cookie message can instill a sense of joyful anticipation. And it seems glumly unrealistic as well.

But I believe that the need to believe in superstitions is akin to the hope or wish to believe in magic. Who doesn’t want to live in a magical universe where only good things happen to good people and bad things don’t exist at all?

According to the New York Times, “The brain seems to have networks that are specialized to produce an explicit, magical explanation in some circumstances, such thinking is only one domain where a relevant interpretation that connects all the dots, so to speak, is preferred to a rational one. Furthermore, it seems that children exhibit a form of magical thinking by about 18 months, when they begin to create imaginary worlds while playing. By age 3, most know the difference between fantasy and reality, though they usually still believe in Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy. By age 8 they have mostly pruned away these beliefs, and the line between magic and reality is about as clear to them as it is for adults.”

Last night, as I was walking home from work, I felt desperate for a sign. I peered into shop windows, searched for newly hung street posters and listened to couples fleeting conversations as I passed them by. But the messages were indecipherable. My gloom grew. All I could see were the bulging stacks of garbage bags, the needy eyes of passersby, the sad sack reflection of a middle-aged woman in the window of a dry cleaner. When does life get easy? When does life become fair?

I have no answers this Friday afternoon, other than to share one last image on yesterday’s journey home. One unmistakable sign of encouragement: that of the sprouting buds. The fledgling shoots and unfurling bulbs have arrived. As I turned the corner to my apartment I remembered: Spring is upon us. Whatever lack of magic I could muster in my mind, signs of life remain, unfettered in their self-sufficiency, unruly in their cheer.

Dedicated to Luba Lukova