Commentary: Always My Fault

I am the kind of person who tends to think that everything is my fault. If someone is upset, I wonder what I might have done to upset them, if a client isn’t happy I conclude that I didn’t work hard enough to please them, and if the Mets are losing at the bottom of the ninth, I believe that it is (inevitably) because I am watching them. I find that when I watch sports events on television this feeling can be so profound I will intentionally leave the room so that my preferred team can have a reasonable chance to catch up.

I think that my sense of being intrinsically at fault was best evidenced during the 2003 East Coast black out. At the time, I was visiting Boston where the lights remained on. One of my reactions upon hearing of the situation was relief that I wasn’t home in NY when it happened. I did not experience this relief because I still had electricity; rather it was because I could not possibly be held responsible for the five state blow out because I had been blow drying my hair with the air conditioner on.

For most of my life I thought nothing of this psychological impediment; it is only in the last few years that colleagues and loved ones began to suggest that I reconsider this highly narcissistic view of the world. But the biggest obstacle to facing this was finding myself in love with a man that, despite professing undying love for me, seemed to find fault with almost everything I did. He told me that I slouched when I walked, I made too much noise when I ate, I didn’t drink the right cocktails, my wardrobe was matronly, my shoes were cheap and I even clapped too loud in a jazz bar. I did everything I possibly could to change myself: I bought new clothes and shoes, practiced eating with my mouth closed; I even hired a dog trainer to help tame what he claimed were disobedient dogs. Since I thought this man was smarter than me, and since I already believed I was at fault for anything that went wrong around me, I assumed that he was seeing the world—and me—more accurately than I could. What an accomplishment it would be if I could finally, at long last, fix all my flaws!

After a year and a half, I gave up. I was exhausted and bleary-eyed and downright depressed. I was also embarrassed. I still believed that this man was smarter and more sophisticated and erudite than I was, and not only was I sure that his criticisms of me were accurate, I was fearful that everyone that knew us both—especially the really intelligent ones—would shirk away from me and pity the poor girl that let the smart boy get away.

According to Jerome Segal in his wonderful book Graceful Simplicity, “Nearly everybody perceives themselves through the norms of culture. This is why most people consume whatever the marketplace touts, without a second thought. The basic self-esteem of the individual is defined by the consumptive norms of society and of others. Hence, what is outside of them forms their self-identity and their personal norms for behavior, consuming not only products and services but values of worth and self-esteem.”

Self-perception is a complicated and fascinating subject and it is also unavoidable. What I have since learned is people decide on their own attitudes and feelings from observing themselves behave in various situations. This is especially true when internal cues are so weak or confusing they effectively put the person in the same position as an external observer. But Freudian psychology suggests that self-perception is an illusion of the ego, and cannot be trusted to decide what is in fact real. Such questions are continuously reanimated, as each generation grapples with the nature of existence from within the human condition. The questions remain: Do our perceptions allow us to experience the world as it "really is?" Can we ever know another point of view in the way we know our own?

My hard thought answer: I don’t know. In retrospect, I think that my holding the world so close and imagining everything going wrong as my fault was my way of exercising a wish of control: in other words, the harder I worked the more things would be good and safe and comfortable.

Most recently I have become captivated by the tension between the perfect and the imperfect, and the murky matter in between. I am beginning to believe that both intrinsically depend on each other, feed off each other, and in the magical place where they balance, something resides that just might be considered art.

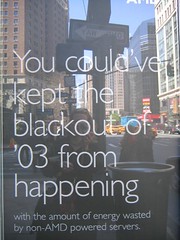

Or perhaps (explained with a tad less grandiosity) it is just something you can learn from. Last weekend, now several years since my break up with the critical ex-boyfriend, I had brunch with a dear friend. Over our meal, she mentioned to me that an incredibly smart and successful mutual acquaintance recently asked her if the man and I were still together. When she told me this, I immediately concluded that he was asking because he felt sorry for me and my romantic travails. When I sheepishly asked what his response was when she told him we weren't together, she laughed and informed me that despite being very happily married, he was so concerned for me during the relationship he had considered trying to rescue me. I laughed in relief and gratitude and gleefully floated back home. But my moment of vanity was short lived. A few days later as I was walking to work, a haunting and familiar headline jumped out at me as I passed an ad on a telephone kiosk. It read, “YOU COULD HAVE KEPT THE BLACK-OUT OF 2003 FROM HAPPENING...” I inched closer and finished reading the copy. In much smaller type, the sentence continued: “...with the amount of energy wasted by non-AMD powered servers.” And for one brief and blissfully perfect second, I rejoiced in the fact that the message wasn’t referring to me and my blow dryer.

I think that my sense of being intrinsically at fault was best evidenced during the 2003 East Coast black out. At the time, I was visiting Boston where the lights remained on. One of my reactions upon hearing of the situation was relief that I wasn’t home in NY when it happened. I did not experience this relief because I still had electricity; rather it was because I could not possibly be held responsible for the five state blow out because I had been blow drying my hair with the air conditioner on.

For most of my life I thought nothing of this psychological impediment; it is only in the last few years that colleagues and loved ones began to suggest that I reconsider this highly narcissistic view of the world. But the biggest obstacle to facing this was finding myself in love with a man that, despite professing undying love for me, seemed to find fault with almost everything I did. He told me that I slouched when I walked, I made too much noise when I ate, I didn’t drink the right cocktails, my wardrobe was matronly, my shoes were cheap and I even clapped too loud in a jazz bar. I did everything I possibly could to change myself: I bought new clothes and shoes, practiced eating with my mouth closed; I even hired a dog trainer to help tame what he claimed were disobedient dogs. Since I thought this man was smarter than me, and since I already believed I was at fault for anything that went wrong around me, I assumed that he was seeing the world—and me—more accurately than I could. What an accomplishment it would be if I could finally, at long last, fix all my flaws!

After a year and a half, I gave up. I was exhausted and bleary-eyed and downright depressed. I was also embarrassed. I still believed that this man was smarter and more sophisticated and erudite than I was, and not only was I sure that his criticisms of me were accurate, I was fearful that everyone that knew us both—especially the really intelligent ones—would shirk away from me and pity the poor girl that let the smart boy get away.

According to Jerome Segal in his wonderful book Graceful Simplicity, “Nearly everybody perceives themselves through the norms of culture. This is why most people consume whatever the marketplace touts, without a second thought. The basic self-esteem of the individual is defined by the consumptive norms of society and of others. Hence, what is outside of them forms their self-identity and their personal norms for behavior, consuming not only products and services but values of worth and self-esteem.”

Self-perception is a complicated and fascinating subject and it is also unavoidable. What I have since learned is people decide on their own attitudes and feelings from observing themselves behave in various situations. This is especially true when internal cues are so weak or confusing they effectively put the person in the same position as an external observer. But Freudian psychology suggests that self-perception is an illusion of the ego, and cannot be trusted to decide what is in fact real. Such questions are continuously reanimated, as each generation grapples with the nature of existence from within the human condition. The questions remain: Do our perceptions allow us to experience the world as it "really is?" Can we ever know another point of view in the way we know our own?

My hard thought answer: I don’t know. In retrospect, I think that my holding the world so close and imagining everything going wrong as my fault was my way of exercising a wish of control: in other words, the harder I worked the more things would be good and safe and comfortable.

Most recently I have become captivated by the tension between the perfect and the imperfect, and the murky matter in between. I am beginning to believe that both intrinsically depend on each other, feed off each other, and in the magical place where they balance, something resides that just might be considered art.

Or perhaps (explained with a tad less grandiosity) it is just something you can learn from. Last weekend, now several years since my break up with the critical ex-boyfriend, I had brunch with a dear friend. Over our meal, she mentioned to me that an incredibly smart and successful mutual acquaintance recently asked her if the man and I were still together. When she told me this, I immediately concluded that he was asking because he felt sorry for me and my romantic travails. When I sheepishly asked what his response was when she told him we weren't together, she laughed and informed me that despite being very happily married, he was so concerned for me during the relationship he had considered trying to rescue me. I laughed in relief and gratitude and gleefully floated back home. But my moment of vanity was short lived. A few days later as I was walking to work, a haunting and familiar headline jumped out at me as I passed an ad on a telephone kiosk. It read, “YOU COULD HAVE KEPT THE BLACK-OUT OF 2003 FROM HAPPENING...” I inched closer and finished reading the copy. In much smaller type, the sentence continued: “...with the amount of energy wasted by non-AMD powered servers.” And for one brief and blissfully perfect second, I rejoiced in the fact that the message wasn’t referring to me and my blow dryer.