Commentary: Painful

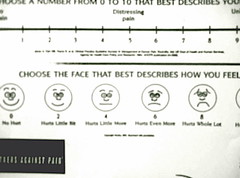

For the last three days I have been in the Georgetown University Hospital taking care of my friend Susan, who was undergoing surgery. The hospital is one of the best in the country and the care they gave my friend was formidable. Aside from their fastidious and obsessive attention to cleanliness (there was a serious hand washing policy enforced as the nurses visited each patient on the floor; and even flowers were forbidden in the rooms) there was also particular attention paid to pain. Someone in the hospital’s design department created a poster that was prominently displayed with the headline “Are You In Pain?’ and it included the following copy: “If you are in pain, you have the right to proper pain management. Talk to your doctor or nurse about it. Here’s why: No one should have to live with pain. There are medications that really work. The doctor or nurse can’t help you unless you tell them about your pain.”

Featured on the poster were ten face icons. They were numbered 1-10 and they ranged from a pleasant happy face to a face in utter agony. Each icon was numbered and corresponded to the amount of pain a person could be in; one was no pain, five was distressing pain and ten signified unbearable pain. The purpose of the graphic was to allow a patient to simply point to the emoticon that correlated to the amount of pain they were in. This, of course, got me thinking about the subjective vs. objective nature of pain, and how quickly we are, in our culture today, to articulate discomfort or annoyance or any number of pains we might believe constantly plague us.

Aside from the very measurable amount of pain patients are in, there is something else a visitor encounters in abundance while being in a hospital for a number of days. Time. Time moves very slowly in a hospital. There are no cell phones or computers allowed, and if the loved one you have come to visit or care for is in surgery or sleeping, there is very little to do. Mostly, during my experience at Georgetown University Hospital, I sat around thinking. I also continued my journey through Eric Kandel’s incredible autobiography “In Search of Memory.” In his book, Kandel charts the intellectual history of the emerging biology of the mind and illuminates how behavioral psychology, cognitive psychology, neuroscience and molecular biology have converged to allow us to understand how memories are formed and where they actually reside in our brains. For the work he did in this field, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2000.

When I couldn’t read anymore, I walked the halls and perused the posters about coping with things like survival and advanced cancer and stem cell transplantation and bereavement. And I felt guilty about how lucky I am and how much I take for granted being healthy. I thought about how hard I have been working this past year and I wondered exactly what I have been doing. I wondered why, as a culture, we seem to use busy-ness as a badge of honor. I questioned if I needed to be busy in order to feel worthy of being alive and wondered if there was anything I was using my uber-busy schedule to distract me from thinking about. When I got back to Kandel’s book, the answer magically fell before me. In describing his need to constantly run more experiments in order to feel that he was continually accomplishing something, he realizes that it is taking a toll on his marriage. He corrects the error of his ways just in the nick of time and he confides the following: “As a consequence I learned the obvious lesson that hard thinking, especially if it leads to even one useful idea, is much more valuable than simply running more experiments.” Kandel is then reminded of a comment made about the scientist Jim Watson by Max Perutz, the Viennese-born British structural biologist: “Jim never made the mistake of confusing hard work with hard thinking.”

On the train ride home to New York, I sat in a seat next to two real estate moguls traveling together who talked on their cell phones for the entire 2:50 minute trip. When the conductor came around to collect our tickets, one of the gentlemen couldn’t find his ticket and wouldn’t get off of his phone as he searched through his bags and pockets. Finally he told the conductor that he had lost his ticket. As he begrudgingly hung up his phone, he looked at me and sneered as he quipped: “freakin’ pain in the ass.” At that moment all I wanted to do was to whip out the trusty pain poster that Susan’s nurse let me take, and ask him where his “freakin’ pain” might reside on a scale of 1-10.

Featured on the poster were ten face icons. They were numbered 1-10 and they ranged from a pleasant happy face to a face in utter agony. Each icon was numbered and corresponded to the amount of pain a person could be in; one was no pain, five was distressing pain and ten signified unbearable pain. The purpose of the graphic was to allow a patient to simply point to the emoticon that correlated to the amount of pain they were in. This, of course, got me thinking about the subjective vs. objective nature of pain, and how quickly we are, in our culture today, to articulate discomfort or annoyance or any number of pains we might believe constantly plague us.

Aside from the very measurable amount of pain patients are in, there is something else a visitor encounters in abundance while being in a hospital for a number of days. Time. Time moves very slowly in a hospital. There are no cell phones or computers allowed, and if the loved one you have come to visit or care for is in surgery or sleeping, there is very little to do. Mostly, during my experience at Georgetown University Hospital, I sat around thinking. I also continued my journey through Eric Kandel’s incredible autobiography “In Search of Memory.” In his book, Kandel charts the intellectual history of the emerging biology of the mind and illuminates how behavioral psychology, cognitive psychology, neuroscience and molecular biology have converged to allow us to understand how memories are formed and where they actually reside in our brains. For the work he did in this field, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2000.

When I couldn’t read anymore, I walked the halls and perused the posters about coping with things like survival and advanced cancer and stem cell transplantation and bereavement. And I felt guilty about how lucky I am and how much I take for granted being healthy. I thought about how hard I have been working this past year and I wondered exactly what I have been doing. I wondered why, as a culture, we seem to use busy-ness as a badge of honor. I questioned if I needed to be busy in order to feel worthy of being alive and wondered if there was anything I was using my uber-busy schedule to distract me from thinking about. When I got back to Kandel’s book, the answer magically fell before me. In describing his need to constantly run more experiments in order to feel that he was continually accomplishing something, he realizes that it is taking a toll on his marriage. He corrects the error of his ways just in the nick of time and he confides the following: “As a consequence I learned the obvious lesson that hard thinking, especially if it leads to even one useful idea, is much more valuable than simply running more experiments.” Kandel is then reminded of a comment made about the scientist Jim Watson by Max Perutz, the Viennese-born British structural biologist: “Jim never made the mistake of confusing hard work with hard thinking.”

On the train ride home to New York, I sat in a seat next to two real estate moguls traveling together who talked on their cell phones for the entire 2:50 minute trip. When the conductor came around to collect our tickets, one of the gentlemen couldn’t find his ticket and wouldn’t get off of his phone as he searched through his bags and pockets. Finally he told the conductor that he had lost his ticket. As he begrudgingly hung up his phone, he looked at me and sneered as he quipped: “freakin’ pain in the ass.” At that moment all I wanted to do was to whip out the trusty pain poster that Susan’s nurse let me take, and ask him where his “freakin’ pain” might reside on a scale of 1-10.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home